One Stream At A Time

In the 100 years after the civil war we lost countless small streams and rivers to agriculture and urbanization one stream at a time over 1000’s and 1000’s of landscapes in America. This is the story of restoration of one of those streams, Sixmile Creek. Earth Day 2022 was Friday April 22 so this and the next blog will cover efforts by me and my graduate students to make earth a little better, one stream at a time.

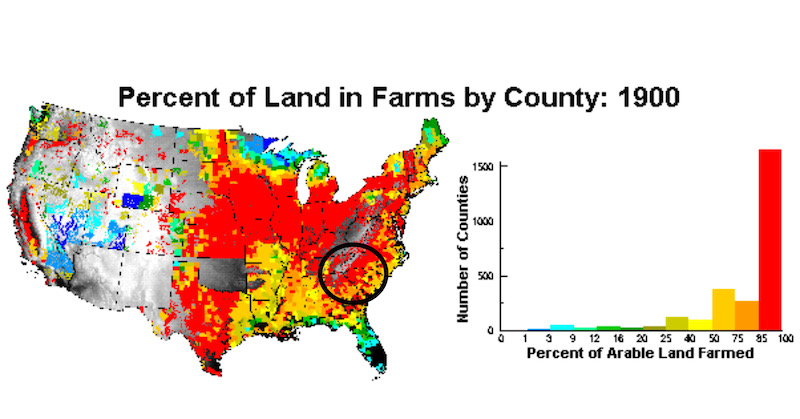

By the time the Great Depression (1929-1939) happened much of the agricultural lands in the southeast U.S. and Midwest U.S. were in just as bad condition as the U.S. economy. Agricultural practices in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s had depleted soils of the characteristic which sustain agriculture. After the Civil War nearly 2/3rds of farmlands in the upstate of South Carolina were farmed by tenant farmers and sharecroppers who did not own the land and had no incentive to protect the land for future generations. The percentage of lands converted from forests to agriculture peaked. Across the South and the Midwest, a terrible drought struck. The years 1930 and 1931 had been unusually dry, but 1934 brought drought to 80 percent of the U.S., and extreme drought returned in 1936, 1939, and 1940. Soil erosion was widespread. There were no systematic studies made during those years so scientists can only speculate about stream and river water quality.

President Roosevelt signed the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act in 1937. The purpose of the law included the ability of the federal government to purchase “sub-marginal” lands no longer fit for agricultural use and then utilize that land for other more suitable purposes including conservation programs.

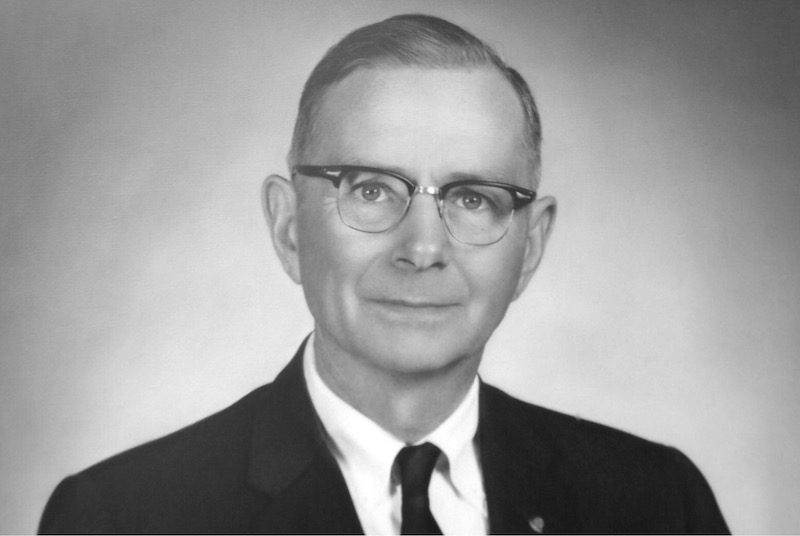

The history of the Clemson Forest was rooted in the Great Depression of the 1930’s. It was the efforts from Dr. George Aull (Agricultural Economics) that got the whole thing started. The Clemson Experimental Forest is the product of the “Clemson Community Conservation Project” (CCCP) initiated by Dr. Aull.

The Project was funded by the Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal programs, and later by the Bankhead – Jones Farm Tenant Act. Nearly 30,000 acres of worn out farmlands around Clemson College were purchased under the project. Then, in 1954, the project was deeded to Clemson College, thanks to the efforts of U.S. Senators Charlie Daniel, Strom Thurmond, State Senator Edgar Brown and Dr. George H. Aull. The Clemson Experimental Forest was born.

All across the Southeast U.S. damaged lands also damaged small streams which lost their riparian vegetation. The riparian vegetation stabilized stream side soils and kept streams cool because of shade provided by the trees. The vegetation was also the fuel for the stream food web. Food webs in stream ecosystems were not understood until the 1970’s. After the abandonment of farms many lands underwent secondary succession and slowly recovered; and so did the water quality of their streams. The CCCP included reforestation efforts of the lands around Sixmile Creek. Small tributaries in areas which were too steeply-sloped for farming provided safe haven for some but not all fish species to re-populate recovering streams. Downstream rivers also provided a means for tributary streams to recover fish species providing no impediments for upstream migration were constructed.

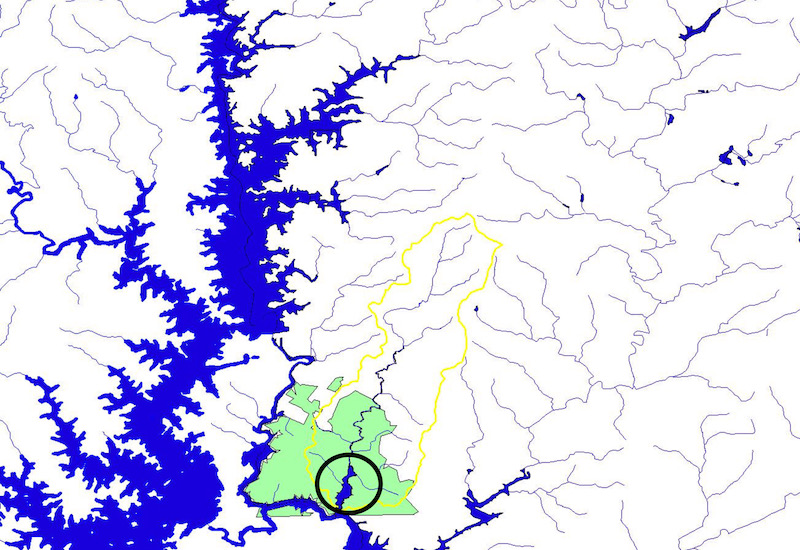

Sixmile Creek was a special situation as were so many other streams in the U.S. During the Great Depression and decades before reforestation had a chance to improve stream water quality and habitat a reservoir was built near the confluence of Sixmile Creek with the Keowee River. The dam was a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) (1933-1942) project to put unemployed persons to work. The dam created Lake Issaquena (1934). But the dam also prevented migration of fish from the Keowee River back into Sixmile Creek. The timing could not have been worse. At the precise time when the landscape would begin a multi-decade healing process the dam was created where the stream entered the Keowee River. The dam permanently isolated Sixmile Creek from all other riverine ecosystems. In nature and undisturbed by man, riverine ecosystems are a complex network of inter-connected, flowing waters which transport water and materials downstream collecting into larger streams and rivers. But passage by fishes is possible in both directions. Then in the mid-1950’s Lake Hartwell’s dam impounded the Seneca River, the lower Keowee River and lower Twelve Mile River. But the Issaqueena Dam was impassable for fish, so Lake Hartwell did not directly impact Sixmile Creek because it was preceded by the Issaqueena Dam. The lands surrounding Sixmile Creek had experienced agricultural abuse in the 1800’s and early 1900’s and some fish species losses were now permanent because of Sixmile Creeks isolation created by the presence of Lake Issaquenna and its dam.

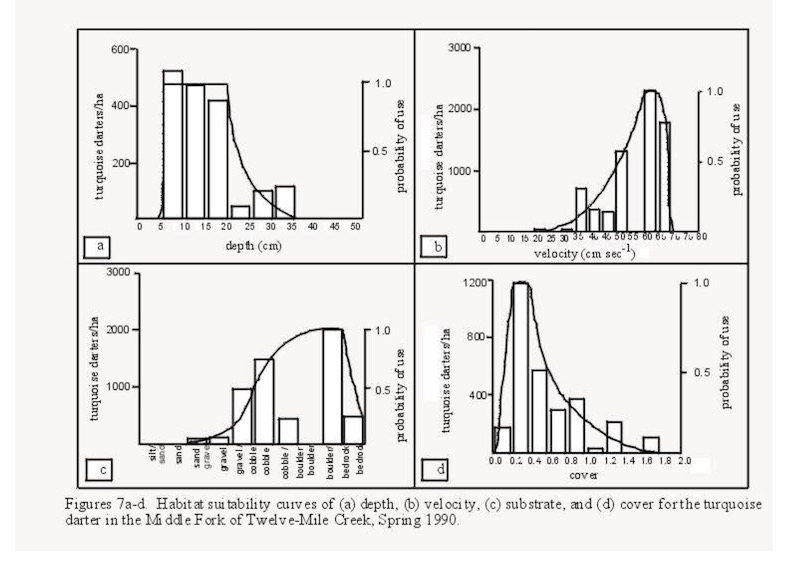

When I started teaching at Clemson University in 1978 only one other fisheries Professor had preceded me in that position. He had made several fish collections in Sixmile Creek and surrounding streams. His specimens were deposited in the Fish Collections of the “Vertebrate Museum” at Clemson University. The SC DNR biologist with an office near Clemson had a primary responsibility as “Trout Biologist” which meant his efforts focused on the trout waters in SC’s mountains. I was teaching Ichthyology in one semester and Fishery Biology during the other semester. Both classes included weekly field trips. So I set about sampling the streams of Pickens County including Sixmile Creek in Clemson’s Experimental Forest. After about 20 years of sampling I thought it was peculiar that Sixmile Creek was missing the the two species of darters found in all surrounding streams and rivers: turquoise darters and blackbanded darters, particularly the turquoise darter which thrived in similarly sized streams nearby. Later when I considered the history of Sixmile Creek it all made sense. In 1990 my first student working on darters (Jay Delong, M.S. 1991) developed “Habitat Suitability” models for the Turquoise Darter and several other small non-game species using a pristine tributary of Twelvemile River.

Habitat Suitability models show preferred habitat characteristics of a species. The models are built by tedious sampling of small quadrants or plots of a stream and comparing the abundance of the species in question to the habitat characteristics for that plot. The primary habitat characteristics measured are substrate, depth, and velocity providing temperature and oxygen are suitable. “Habitat Suitability” models were being developed all across the country for the purpose of regulating or maintaining minimum discharges below hydroelectric dams in order to provide habitat for fish species. Jay’s Delong’s Habitat Suitability models would be used by my second student to evaluate Sixmile Creek’s habitat suitability for restoration of Turquoise Darters, design a “re-introduction plan” and initiate the plan (next blog).

Leave a comment